Have you ever stood in the cereal aisle, overwhelmed by the variety of options, and wondered why your hand reached for the cheerfully labeled box of “Honey Bunches of Oats” instead of the cheaper, unbranded “corn flakes”?

If you’re curious about the unseen forces that drive our daily choices, or if you’re looking for knowledge to help you better market your products or services, then prepare to dive deep into the fascinating world of “Predictably Irrational.”

The old world of classical economists believed that us humans are “rational actors.” That we are logical, profit-maximizing beings that make optimal decisions in every scenario. But that couldn’t be farther from the truth!

Our decisions are often far from rational—they are guided by a host of biases, emotions, and subconscious influences that we are totally unaware of! However, there’s a twist—our irrationality is NOT random, but follows predictable patterns that can be studied and understood. That makes us, for better or worse, able to be manipulated.

But most importantly, “Predictably Irrational” unravels some of the mystery of why we buy “Product X” over “Product Y,” and that makes it a must-read whether you are:

- An entrepreneur looking to boost sales,

- A business leader looking to understand customer behavior,

- Or just someone fascinated by the quirks of human decision-making.

Who is Dan Ariely?

Dan Ariely is a renowned professor of psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University, and before that at MIT. He earned two Ph.D.’s—one in cognitive psychology and another in business administration. His research and writing have been published in many academic journals and mainstream media, including a 10-year column in the Wall Street Journal. His academic research builds upon a larger field called “behavioral economics” that was co-founded by Daniel Kahneman.

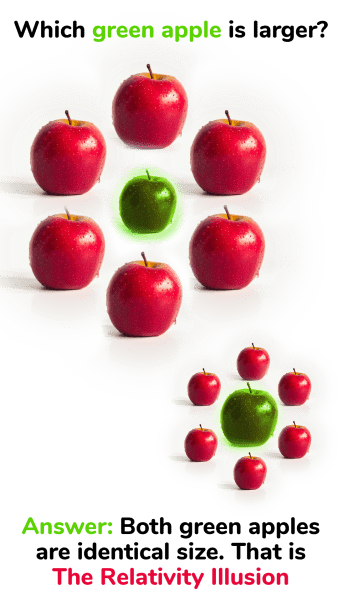

⚖️ 1. The Relativity Illusion: We tend to judge things not objectively, but in comparison to what else is nearby

Ever wondered why you’d drive across town to save $7 on a nice lunch, by wouldn’t blink an eye at that same $7 tacked onto the price of a $300 coat? Welcome to the strangely elastic and inconsistent world of human judgment!

At the heart of “The Relativity Illusion” lies a simple truth – we humans are creates that compare, we find it hard to evaluate things in a vacuum, “objectively.” We generally determine the worth of something not in isolation, but by contrasting it with what’s nearby.

Let’s dive into a famous example from “Predictably Irrational.” Dan Ariely spotted something peculiar on The Economist’s website. They had three subscription options:

- $59 for digital-only,

- $125 for print-only, and

- $125 for both digital and print.

Ariely smelled a marketing trick. Who’d choose print-only when they could get both for the same price? He dubbed this the “decoy option”—a ploy to make the expensive option seem like a bargain.

To test this, Ariely polled the students in his large university class. When all three options were presented, most picked the more expensive $125 combo and nobody would buy the middle option. But when he removed that decoy middle option, the majority went for the cheaper $59 digital-only option. His suspicions were confirmed!

This trick is often used daily in real-world business settings, like your favorite restaurant. The book mentions Gregg Rapp, a renowned restaurant consultant, who uses a similar trick in menu pricing. He adds one very high-priced item to the menu, making the rest of the items seem affordable by comparison.

Online entrepreneur Alex Hormozi, who’s sold over $100 million in products, reveals a powerful sales hack in his book, “$100M Offers.” He calls it “The Stack.”

Just like those old infomercials that piled on freebies with a “but wait there’s more!” Hormozi gradually presents an offer, adding each piece to a chart. By the end, it feels like it’s worth, say $200. But then, he reveals a real price of just $20. The stark contrast makes customers feel like they’re snagging an amazing deal.

The Relativity Illusion is the concept that humans tend to make judgments in a relative way, compared to what else is available nearby.

⚓ 2. The Anchoring Effect: How initial ‘anchors’ or reference points manipulate our choices and spending

Have you ever wondered why Starbucks can charge 30% more for a ‘grande’ coffee that’s not all that different from a ‘large’ elsewhere? Or why black pearls, once almost worthless, now sell for a small fortune? Welcome to the fascinating idea of the ‘Anchoring Effect.’

The ‘Anchoring Effect’ is a trick of persuasion, where a certain focal point or ‘anchor’ is used to sway our comparisons and decisions.

As we’ll see, this concept fits in well with Dan Ariely’s larger philosophy that our minds can be swayed in quite irrational ways. But it is contrary to the traditional economic belief that pricing is determined by supply and demand.

Let’s look at some examples:

- Black pearls, they used to be almost worthless. Until 1973, when the clever businessman Salvador Assael, aka the “pearl king,” applied the right marketing strategy. He displayed black pearls alongside diamonds and rubies in fancy ads and in posh New York shop windows. This ‘anchoring’ with luxury items transformed black pearls into coveted luxury items.

- Starbucks drinks, they use a different trick to avoid the wrong anchors. By naming drink sizes as ‘short’, ‘tall’, ‘grande’, ‘venti’ – they avoid a direct comparison with the usual ‘small’, ‘medium’, ‘large’ from competitors. This makes it easier for them to charge more.

- “Arbitrary Coherence” is Dan Ariely’s name for an extreme version of the Anchoring Effect. In a study, he had people write down the last two digits of their social security number, right before bidding in an auction. The results were shocking! Those with higher digits (80-99) bid 216% more than those with lower digits (00-19)! So, for example, someone with a social security number ending in “08” might bid $9 on a bottle of wine, while someone with digits ending in “95” would bid around $25! All because that arbitrary anchor had been set before their bidding.

Thinking, Fast and Slow is another book you would probably love, on the cognitive biases that people have. It was written by Daniel Kahneman, who basically created this field of ‘behavioral economics’ and even won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. So, that book also talks about the “Anchoring Bias,” demonstrating how our decisions can be heavily influenced by initial information. For instance, in a price negotiation, the first number that is mentioned often “anchors” or steers the rest of the discussion, even if it is unreasonably low or high.

The ‘Anchoring Effect’ is a potent psychological principle that demonstrates how our judgments can be swayed by initial reference points, impacting how much we’re willing to pay for something.

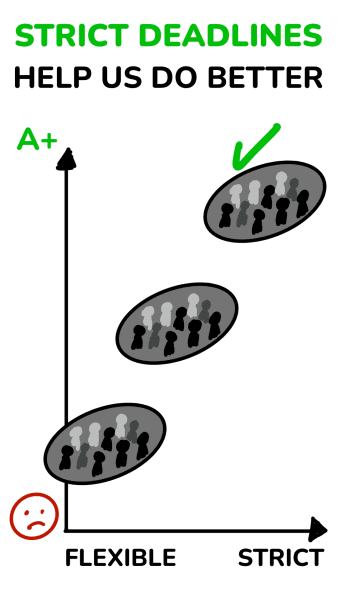

⏳ 3. The Deadline Paradox: Strict deadlines make us less vulnerable to procrastination and help us do better work

I can’t be the only one who remembers putting of school projects until the very last minute, working on them into the night? In this next section, we’ll discuss why procrastination happens and some smart strategies to avoid it.

Procrastination is essentially a problem of delayed gratification, it is when we give in to immediate temptations rather than sticking to long-term plans.

One of Dan Ariely’s most insightful experiments in “Predictably Irrational” demonstrates the power of strict deadlines. During one semester, he had three separate classes, and each student had to submit three papers over 12 weeks.

- The first class was told they had no deadlines for each paper, they only needed to be handed in by the end of the semester.

- The second class was able to set their own deadlines for each paper, decided beforehand when they would be due. In other words, they would ‘pre-commit’ to certain dates.

- The third class was given strict deadlines for each paper, spaced 4 weeks apart.

The result? The third class with fixed deadlines got the best grades. Next was the second class, who set their own deadlines. And the first class, that was given ultimate flexibility, did worst. Why? It’s likely that not having any deadlines caused students to procrastinate more, many of whom ended up rushing through all the papers at the very end of the year.

Here are some more clever strategies to beat procrastination:

- Pre-commitment. Beat impulsive urges by ‘pre-committing’ to decisions in your cool, rational state. For example, set up automatic paycheck deductions for savings or schedule gym sessions with a buddy.

- Bundling. Simplify preventive tasks to get them done. For example, Honda and Ford car dealerships found that bundling regular maintenance at set kilometre intervals (like at 5,000km, 10,000km, etc.) caused a lot more people to come in for the services. Ariely suggests the healthcare system should do the same thing, bundling tests and checks, in the end saving lives and money.

- Force delayed gratification. Some folks follow the “ice glass method,” freezing their credit card in ice to prevent impulsive buying. Ariely suggested a high-tech self-control credit card, but the bank executives he spoke to didn’t go for it—likely because they profit $16 billion per year from interest!

- Combine pain and pleasure. Ariely once had to give himself 6 months of daily injections, as part of an experimental study treating Hepatitis C (from an infection he’d acquired in a hospital). Almost nobody in the study completed the injections as prescribed, because they caused 16 hours of unpleasant side effects, like nausea and vomiting. But the author did it, by immediately watching movies—his favourite hobby—right after each injection.

In the incredibly popular book Atomic Habits, the author James Clear shares the same tip under the name “Temptation Bundling.” He says, “You’re more likely to find a behavior attractive if you get to do one of your favourite things at the same time.”

For example, if you need to get in shape and you love watching comic book movies, then only allow yourself to do this while exercising. One engineering student from Ireland named Ronan Byrne took this idea to the next level, connecting his stationary bike to his television, so he could only watch Netflix while working out!

Procrastination is really a problem of choosing impulsive gratification over long-term goals. Our best friend in beating this enemy include strict deadlines, pre-commitments, and temptation bundling.

💸 4. The FREE! Trap: How our obsession with “FREE!” can cost us more than we realize

Have you ever been shopping online and added items to your cart just to qualify for free shipping? Or maybe you’ve signed up to a free trial, but forgot to cancel before the first payment? Or how about waiting 45 minutes in line for something like a free ice cream cone?

You’ve been caught in the irresistible attraction of “The FREE! Trap.” This powerful principle reveals how we often end up paying more in time, effort, and even money… for things that are “free.”

In a series of fascinating studies, Dan Ariely illustrates that when something is offered for “free,” then people become irrationally excited. For example, people were offered small chocolates, either at negligible prices or free. And he found that the difference between two cents and one cent was far less impactful than the giant leap from one cent to free. This flies in the face of traditional economic theories that may predict a “rational actor” to value a one cent discount equally in both situations.

But there’s powerful psychology at work when we hear the word “FREE!”, says Dan Ariely. FREE! implies there is no risk, no downside, no chance of making a mistake and appearing foolish.

Therefore, we often go out of our way to get the free offer, whether that means waiting ages in line for that free ice cream, elbowing our way through crowds on a free museum day or adding items to our shopping cart to qualify for that “free” shipping. Amazon saw this firsthand—Their sales got a nice boost in every country they offered free shipping. But in France, they tried charging 20 cents for shipping, and were disappointed with no sales boost… until they finally dropped that tiny fee.

(Learn more about Amazon’s business innovations rise to dominance in our summary of the great book The Everything Store.)

Obviously, all the “free” examples we’ve mentioned carry a cost—in time, effort, and even money. And that’s the point. We should beware of these hidden costs of FREE. However, there may be ways to utilize the power of a free offer, for social good and ethical business:

- Social policies. If societies and governments really want to motivate people towards a behavior, like getting preventive health checkups, they could make those free, rather than low-cost. Or they could make the registration for electric vehicles free, as a sweet bonus for helping reduce pollution.

- Business offer. Offering something free can be a surefire way to grab attention, whether it’s a sample of your product or a small part of your service…

Interestingly, the advertising giant Claude Hopkins, known as the father of “Scientific Advertising,” was also a huge fan of “free.” Around 100 years ago, he was the mastermind behind famous brands we still recognize today, like Quaker Oats and Palmolive Soap.

Hopkins believed that free samples are un unbeatable marketing tool. He dismissed other types of offers, like 50% discounts or 2-for-1 deals, for being dramatically less effective. And although giving out free samples may seem costly, Hopkins argued it actually reduced customer acquisition costs. Why? Because slapping “Free” on your ad boosts readership and response like nothing else!

Read more in our summary of Scientific Advertising by Claude Hopkins

The FREE! Trap reveals how the attraction of ‘free’ can often cloud our judgment, prompting us to spend more in time or effort than we would otherwise.

💔 5. Social Vs. Market Norms: Two very different ways of motivating people, “for cause or cash”

Have you ever wondered why it’s okay to bring a bottle of wine to your mother-in-law’s dinner, but not okay to give her cash for the meal? This is exactly the scenario described in “Predictably Irrational” to illustrate the two different worlds of Social Norms and Market Norms:

- In the world of social norms, people build relationships through mutual exchange of favours, gifts, gestures, etc. It’s warm and fuzzy, and cash is out of the picture.

- In the world of market norms, however, brings much different behaviors and expectations. This is the world of payments, prices, and wages. Cold, calculated, and efficient.

A key point: These two worlds don’t mix well. It’s like oil and water. Just like the example just mentioned of paying a family member cash in gratitude for a nice dinner. Most of us probably cringe hearing that example.

It’s commonly accepted that people will work harder “for cause than cash”—when they feel part of a company that is doing good, rather than simply collecting their paycheck. In one of Dan Ariely’s experiments, he found people would actually work harder at a repetitive computer task when they were asked to do it “as a favour,” instead of being paid 5 dollars! Another fascinating example: when lawyers were asked to work for cheap ($30/hour) to help retirees, most refused… but when they were asked to work for retirees for free, then the vast majority accepted! I think there’s no better illustration of the two different worlds than that.

Many companies are trying to introduce more social norms into the workplace, this feeling like “we’re all in this together as a family.” Top companies like Google retain the best talent by appearing to take care of their workers with the best health insurance, fancy lunch services, and other benefits that seem lavish. However, these kind of social contracts break down, says Dan Ariely, when companies make sudden moves to downsize and cut costs—essentially saying “we won’t be there for you,” so the employees don’t feel a social obligation to remain loyal, either.

The ultimate business book that explores this concept further is Start With Why by Simon Sinek, why says that leadership in business is all about creating a shared purpose or “why.” Sinek explains, “People don’t buy what you do; they buy why you do it. And what you do simply proves what you believe.” In other words, we are drawn to causes that resonate with us and to organizations and people that align with our values.

Apple, under Steve Jobs’ leadership, is a perfect example of ‘starting with why.’ Jobs’ vision to ‘think different’ and challenge the status quo resonated deeply with people, turning Apple into more than just a tech company—it became a symbol of individuality and innovation.

In essence, our behavior can be governed by either social norms or market norms. While market norms are more efficient, we generally bring more effort and creativity when working “for cause than cash,” explaining the push of many companies to create a family feeling.

🔥 6. The Passion Problem: How entering a “hot state” distorts our decision-making

You might think you know yourself pretty well, right? But what about when you’re in a “hot state,” like when you’re angry or aroused? Do you really know that version of yourself? Welcome to “the problem of passion,” where we uncover how our decision-making can wildly vary based on our emotional state.

In his book, Ariely reveals an experiment done with college male students that is both insightful and, uh, a little gross. The students were sent home with a laptop covered with clear plastic wrap and they were told to fill out a questionnaire on the computer. First, they would answer the questions in a “cold” rational state. Then they were told to look at arousing images and masturbate to get into a “hot” state, while answering the same questions again.

Many of the questions were related to sex, and the difference in response between cold and hot states was striking. After getting in a hot state, the students were 25% more likely to engage in risky behaviors like not using a condom, and they were also 72% more likely to be attracted to women far outside their own age.

The takeaway? We can’t rely on our “cool state” self to handle “hot state” situations. Pledges like “just say no” often fail when our passionate side takes over.

So, what can we do?

- Walk away from the situation before the passion arises. Dan Ariely points out that overcoming passion once it has been ignited, is far more difficult than avoiding it in the beginning.

- OR be prepared regardless of your expectations. For example, by always having a condom handy, regardless of your predictions in a “cold” state of what will happen.

In a nutshell, “The Passion Problem” says that we really have multiple selves, and we cannot rely on our “cool state” rational self to handle “hot state” situations of high passion.

🏡 7. The Ownership Bias: Why we overvalue the things we own

Have you ever heard of “The Ikea Effect”? It’s a fascinating phenomenon where we place higher value on things we’ve put time and effort into creating ourselves.

Think about the last piece of Ikea furniture you assembled. Despite the sweat, possible swearing, and that one mysterious leftover screw, once you finished, you likely felt a sense of pride and accomplishment. And that self-assembled bookshelf or table suddenly becomes more valuable to you than a similar one bought pre-assembled. That’s the Ikea Effect in action! We inherently value our own labor and it amplifies our attachment to the end product.

Welcome to the world of “ownership bias,” a fascinating quirk of human psychology that makes us overvalue what we already possess.

At Duke University, where Dan Ariely works, they are crazy about their basketball team, with groups of students camping outside for nights in hopes of winning game tickets. In one experiment, Ariely asked students who had managed to get a ticket how much they would sell it for, and they said $2,400. Then he asked other students that had camped out for the same time how much they would buy a ticket for, and they said only $170! That’s ownership bias in action!

The author found students with a ticket focused on the lifelong memory it would bring, while those without a ticket focused on alternative uses for the money—like a fun night out with lots of beer and wings.

Let’s explore some practical applications of the ownership bias for finance and business:

- Sales strategies. Offering extended “trial periods” or generous money-back guarantees can exploit the ownership bias. Once a customer takes a product home and begins to feel a sense of ownership, they start to value it more, making it less likely they’ll return it.

- Auction psychology. When we participate in an auction, we often start imagining owning the item we’re bidding on. Thus, we may find ourselves in a bidding war to avoid the disappointment of “losing” our imagined possession.

- Investing. I’m also reminded of the ‘sunk cost fallacy’ often mentioned by finance and investing authors. Once we’ve invested in an asset, we may stubbornly hold onto it, even if it’s performing poorly. This is because our perceived value of it is higher than the market’s – we are attached to our investment and often struggle to let go, even when it might be financially sensible to do so.

In short, ‘The Ownership Bias’ is all about understanding that once we own something – be it a basketball ticket, a self-assembled bookshelf, or an opinion – we value it more than others might.

🚪 8. The Cost of Indecision: When keeping doors open holds us back

Ever felt stuck because there are just too many choices? Maybe you’re swiping endlessly on a dating app, or trying to decide whether to switch jobs or cities.

It’s naturally tempting for us to want to keep our options open. But, as Dan Ariely points out, not being able to commit often comes with a cost.

To illustrate this, I’ll share with you a computer game study done by Dan Ariely and others. Players could click on different coloured boxes or “doors” in the game, each offering a payout between 1-10 cents. They could always go back and choose a different door, but doing risked lower payouts. Want to know what happened? Most people followed a strategy of sampling a few doors, then sticking with the one that gave them the highest payout.

Sounds familiar, right? It’s how we typically approach life, try a few different things, then stick with what we like best. Like dating around a bit, then settling down.

Some may argue, “Isn’t it smart not to commit too soon?” Yes and no. While we don’t want to limit ourselves prematurely, there’s also the risk of spreading ourselves too thin. In most career paths, for example, committing to one path allows us to develop skills and relationships in that field, so we can reach a high level.

Author Mark Manson speaks to this in his wildly popular self-help books. After years of non-commitment in his youth – chasing women, traveling the world – he realized the lifestyle he had romanticized had its downsides. Manson now champions the profound value of commitment, saying it unlocks a deeper set of experiences—be it in a profession, location, or relationship.

Read more in our summary of The Subtle Art of Not Giving a …

In short, while humans love keeping options open, ‘The Cost of Indecision’ reminds us that there’s value in commitment. Sometimes, stepping through a chosen door, and closing it behind us, is the best decision we can make.

🧠 9. The Power of Expectations: How our material experiences are shaped by our immaterial beliefs

Have you ever wondered why a meal tastes better when it’s beautifully presented, or why a branded product just seems superior? This lessons is all about how our expectations can significantly influence our experiences in all areas of life, from medicine to music.

Let’s begin with one of the most astonishing phenomena—the placebo effect. This is a phenomenon where people experience an improvement in their medical condition, simply because they’ve received a treatment, even if it was a fake one.

There are many dramatic examples of the placebo effect, in history and up to the present.

- A surprising number of surgeries have turned out to be a placebo. They were done for years because patients reported feeling better, but when studies finally tested the effectiveness against a placebo, they found no benefit. An example from Predictably Irrational: In 2002, a paper was published in The New England Journal of Medicine by Dr. Moseley demonstrating that a common knee surgery for arthritis, on which $1 billion per year is spent, works no better than a placebo! (The placebo, in that case, was putting patients through a fake surgery!)

- The psychological effects or benefits from the placebo effect can be far more dramatic, as we would expect. Professor Dan Ariely writes that a recent study found 75% of the effect from the six leading antidepressants “was duplicated by placebo controls.”

- The price of a placebo appears to increase its effectiveness, according to one of Ariely’s own studies. It goes without saying that is highly irrational! His study involved giving people a fake pain pill called Veladone-RX (really just Vitamin C). When they read the pills cost $2.50 each, then almost all the study participants reported pain relief after taking it. But when they saw the pills cost a measly $0.10 each, only half did.

The real dilemma is that the placebo effect has real value, it often really helps people to feel better or get better. This can create ethical problems, where doctors may prescribe unnecessary medication for the placebo benefits. Such as the overprescribing antibiotics for sore throats, where there is no effectiveness and can lead to dangerous antibiotic resistance.

Marketing is often about creating expectations that shape people’s experiences of a product or service, a different type of placebo effect.

Marketing uses the power of expectations to enhance our satisfaction with a product. It’s not just an illusion – our brain physically responds to a well-marketed product, adding to our enjoyment. For instance, when participants in one study knew they were drinking Coca-Cola (versus Pepsi), their brains showed greater activity in an fMRI machine. This was a real physiological response in their brain to a well-known brand.

So, if we want to make this lesson practical, here are some ideas for business and sales:

- Use language that evokes novelty and excitement. There’s a reason why expensive restaurants have vivid descriptions of their dishes and include random exotic ingredients. For example, instead of just “pasta,” try selling “artisanal Tuscan spaghetti with rich, homemade marinara.”

- Pay attention to your presentation. When you want to show the value of your product or service in the best light possible, it’s all about context. A world-famous violinist was used to playing to sold-out concert halls filled with hundreds of adoring listeners dressed in fancy suits and dresses. As an experiment, he went to play in a Washington subway station, and almost nobody stopped to listen.

- Beware existing mental stereotypes. In one of Dan Ariely’s experiments, students were given beer with a couple of drops of balsamic vinegar added. The students actually like the taste of this beer better, but ONLY when they were not told about the vinegar before tasting!

In a nutshell, the ‘Power of Placebo’ shows us that our expectations can have a significant impact on our real-life experiences. So the next time you find yourself reaching for a branded product or enjoying a meal more because of a fancy description, remember: it might be your expectations at play.

🤝 10. A Dose of Dishonesty: Why most of us will cheat, but only a little, and how to maintain trust in society

Trust is the glue of society. But what happens when hidden catches and little cheats chip away at this trust? The last 3 chapters of Predictably Irrational dive into this issue.

Firstly, let’s talk about ‘free offers.’ Ariely’s experiment offered ‘free money’ to passers-by. Oddly enough, most folks didn’t stop. Only 1% picked a free $1 bill, while 19% took a free $50 bill. It seems we’re often skeptical about ‘free’ stuff, suspecting a hidden catch.

Then there’s cheating. Ariely’s experiments show that most people cheat just a little. For instance, when given a chance to score their own tests, people reported slightly better results than their actual scores. It seems we’re fine with small cheats like taking a pen from work, but would never steal a dollar from the cash register. In a similar way, most of us would feel okay exaggerating our work experience on a resume or height on a dating profile, rationalizing that “everyone else does it.”

But what about non-cash cheating? Another of Ariely’s studies reveals we’re more prone to dishonesty when the stakes are ‘tokens’, not cash. This rings alarm bells for sectors like banking, where digital transactions are commonplace.

How do we combat this? Ariely found that a reminder of an ethical standards, like the Ten Commandments, drastically reduced cheating. He suggests that some professionals, like lawyers, be made to regularly repeat a professional oath to improve honesty.

In a nutshell: while we think of ourselves as honest, small cheats are more common than we’d like to admit. Regular moral reminders can help keep our ethical compass pointed in the right direction.

- Pre-commit for Self-Discipline: Set up firm deadlines and commitments to conquer procrastination or temptation. If you have a workout partner, then you won’t miss a gym day.

- Use the Power of FREE! in Sales: Use ‘free’ offerings strategically in your marketing for enhanced appeal, like free samples, trials, inspections, etc.

- Foster Social Norms for Leadership: Use social norms like reciprocity and trust to foster stronger relationships in your workplace over purely financial transactions. How can you position the work your team does as making the world a better place?

- Ownership Bias in Sales: Offer trials or money-back guarantees to trigger the ownership bias, making your product more valuable to customers.

- Power of Placebo in Sales: Enhance customer satisfaction by creating a compelling brand story or presentation. Remember that vivid descriptions of your product or service, along with exotic ingredients, can increase the value people experience. For example, sell “Parisian baguettes” rather than “buns.”

Community Notes